Inflation Risk, Currency, Forex, Growth, and Crashes: The Intellectual “Survival Kit” Every Investor Must Have

Risk Number 1: Inflation

According to INSEE (the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies), inflation is “the loss of the purchasing power of money which results in a general and sustained increase in prices.” In more concrete terms, with the same amount of money from one year to the next, you can buy fewer goods. Therefore, conclusions must be drawn regarding financial investment.

Your income must therefore evolve in a similar way to inflation to maintain your purchasing power. The reasoning is simple but deserves to be clarified: if the inflation rate is 2%, your income must increase by 2%. In a scenario where inflation is 4% and, at the same time, your investments see an increase of only 2%, you are effectively losing 2% of your purchasing power. And in this regard, compound interest can also work against your purchasing power, worsening the erosion of your income.

This is a fundamental investment lesson: the profits of the companies you invest in must necessarily increase regularly. When choosing companies or investment vehicles, be sure to check the history of dividend or distribution increases. The same goes for the invested capital: the value of the asset must appreciate positively in the long term, and at the very least compensate for the level of inflation.

How do economists talk about inflation? And what are the key recurring terms to know, along with their practical applications? Take the following sentence: the share price of stock X has risen by 4%. But the inflation rate is 2%. In nominal terms (without taking inflation into account), the growth in the value of the stock is 4%. But in real terms, the growth is only 2% (4% – 2% inflation). The application is therefore very concrete for an investor: your income and your capital must increase at least as much as the level of inflation, otherwise you are experiencing a period of impoverishment, and this phenomenon can only be temporary.

Key Takeaways:

- An increase in nominal value corresponds to the increase in the value of an asset without taking inflation into account.

- An increase in real terms takes inflation into account and refers to the actual ability of a financial asset to acquire goods: inflation is deducted from the initial value.

- Investors often suffer from monetary “myopia” and focus on the nominal value of their assets, losing their bearings when the inflation rate increases significantly.

- As an investor, remember that you are constantly fighting against the damaging effects of inflation on your income and your capital. This rule was largely forgotten in Europe due to the low inflation experienced since the 1990s.

Risk Number 2: Currency, Monetary Policies, and Exchange Rate Fluctuations

Currencies are traded on the international foreign exchange market (Forex). Their values constantly fluctuate against each other based on the balance of supply and demand. This situation creates instability in the purchasing power of currencies relative to one another.

Since 1971, the gold convertibility of currencies was ended. The value of each currency therefore rests exclusively on the confidence that businesses, public institutions, and individuals have in each respective currency. This has led to increased volatility in currency values. Furthermore, the monetary policies of major economic powers have evolved since the great economic crises. It was following the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis that the American and European central banks significantly increased the volume of money in the economy.

While these decisions helped prevent a worsening of the economic crisis, they had adverse effects by driving up prices: first for financial assets (stock market bubble) and real estate assets (rising property prices), and then for everyday consumer goods. These monetary policies, which led to the artificial maintenance of very low interest rates and the large-scale purchase of government bonds, generated major side effects. Consequently, investors must account for this situation and consider both inflationary risk (internal risk) and the potential decline of their own currency (external risk).

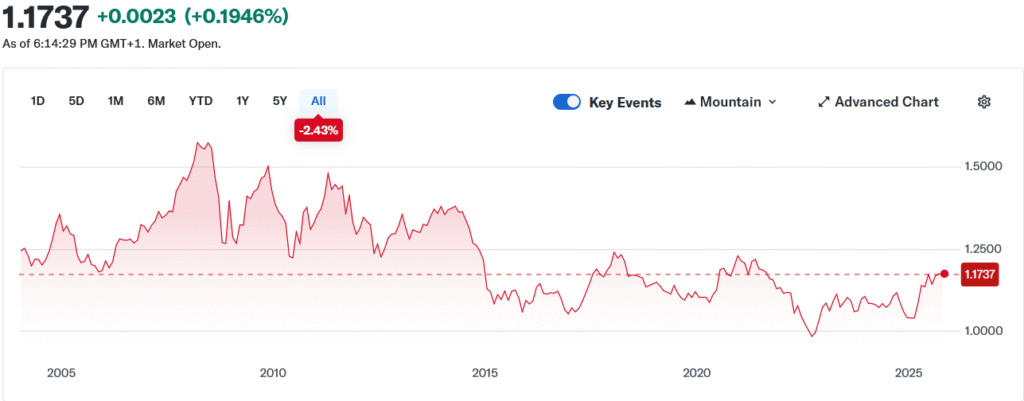

Let’s take a concrete example by observing the variation in the value of the euro against the US dollar. The fluctuations shown in the chart below are extreme and force us to consider the consequences for implementing an investment strategy. Periods of a “strong euro” offer excellent opportunities to buy international assets. Conversely, periods of a “weak euro” make any investment in US dollars very expensive – and thus less opportune. This is a factor everyone must keep in mind when reinvesting income or injecting new savings into their portfolio.

Source: yahoo finance – (Euro vs. Dollar exchange rate chart from 1970 to 2025)

Regarding portfolio income management, holding an international portfolio provides a “cushion” against a falling euro: the income from your foreign holdings is worth more when the euro’s value is lower. On the other hand, their value is lower during periods of a “strong euro,” which weakens your overall income level.

Key Takeaways:

- Since the end of the gold standard, currency volatility has increased, making life more complicated for investors.

- Investors have a strong interest in diversifying their investments internationally by purchasing securities listed in currencies other than the one they live with.

- When building a portfolio and reinvesting income, it is essential to at least minimally monitor the evolution of different currencies.

- Monetary policies have lowered the level of interest rates and have severely diminished the yield of bond investments, reducing the “playing field” for investors seeking to generate income through this means.

Risk Number 3: Fluctuations in Economic Growth

The performance of financial markets is closely linked to the growth of corporate profits. Their long-term trend is positive, but the economy is subject to alternating bull and bear cycles, which have significant consequences for the valuation levels of both stocks and bonds.

In the stock market, the terms “bear” and “bull” are frequently used, corresponding to bull (upward) cycles and bear (downward) cycles. The valuation of your investments, inevitably subject to these cycles, will therefore fluctuate significantly, leading to periods of excessive pride and frustration.

Economic theory has extensively addressed the question of cycles, even if no one fully agrees on their duration or the specific causes of each economic crisis. Regardless, it is a factual reality that phases of growth are systematically followed by phases of recession. The explanation provided by the “Austrian School”1 of the business cycle offers an interesting intellectual framework and bears some similarities to the post-subprime crisis situation.

Initially, interest rates are lowered excessively, providing various sectors of the economy with access to cheap financing. As a result, corporate investment increases, though not always for the most economically and financially sound projects. This surplus of investment generates heightened activity in less essential sectors (for example, high technology at the expense of consumer goods) and creates bubbles linked to this overinvestment. This is followed by a period of inflation (first in financial and real estate assets, then in consumer goods).

Central banks are then forced to raise interest rates – thereby restricting the level of economic activity – to prevent the inflation rate from becoming too high. The “bad investments” are no longer sustainable since demand for goods and services has decreased. Companies then go bankrupt as overall economic activity declines. This is how expansion and recession phases typically follow one another.

Beyond economic cycles, political or other events can also impact the economic cycle. The early 2020s were particularly rich in such events, leading to a cascade of economic phenomena. For example, the health crisis drastically reduced economic activity in 2020, leading to an overheated economy once lockdown periods ended. The recovery in activity caused supply chain problems, which led to shortages and price increases. In a different context, the Russo-Ukrainian conflict exacerbated energy and agricultural commodity problems (primarily grains). The investor must incorporate these elements into their strategy and accept the idea of risk – and, most importantly, its materialization.

Key Takeaways:

- The economy is cyclical by nature, and phases of recession and expansion follow one another.

- Financial markets generally follow a similar pattern: a bubble forms during the expansion period, followed by a crash or correction at the end of the cycle.

- Investors must be clear-eyed about this economic cyclicality and seize opportunities during crises to buy securities that generate higher percentage yields during correction or crash episodes.

Risk Number 4: Financial Crashes

The history of financial crashes is rich with numerous examples. The most well-known are the 1929 crash, the dot-com bubble of 2001, and the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008. But many other events of this nature have been recorded. Regardless, the fact is that the vast majority of actors in trading rooms or those commenting on the price movements of financial assets have not lived through a financial crisis during their careers. The only truly significant bear episode was due to the lockdowns in 2020… and a tremendous rally followed the discovery of vaccines.

In short, it is highly likely that reactions to the next crash will border on stupor and contain a large degree of excess. It is essential to keep this in mind and to remember that a crash also constitutes a moment of opportunity to invest in assets whose prices have fallen. It is both a normal event and an unavoidable rite of passage for long-term investors. The chart below shows the evolution of the DAX 30, the German index comprising the 30 largest companies. The choice of this index is by no means accidental. It is, in fact, one of the few major indices that incorporates the reinvestment of dividends. The CAC 40, for its part, only reflects share prices without dividend reinvestment. This significantly skews comparisons and, above all, makes the analysis of long-term performance less relevant, as dividends constitute a major source of growth for invested capital.

Source: Google finance (Chart: DAX 30 Performance from 1988 to 2022)

This chart is very explicit. Phases of index growth and decline succeed one another, but the long-term trend is clearly upward. With a bit of general economic knowledge, it is possible to identify the major financial crises: the dot-com bubble in 2001, the subprime crisis in 2008, the sovereign debt crisis in the early 2010s, and the COVID-19 crisis in 2020.

Reading a chart is one thing; living through it as an investor is another. The psychological dimension is quite fascinating to observe. Of course, many investors felt immensely more intelligent than their peers in 2000. Those same individuals, after the bubble burst, undoubtedly suffered a blow to their egos. Having “gotten out of trouble” in 2007 after a very strong rally, they then lost a large part of their investment profits in 2008 and began to question the validity of their strategy. It then took until the mid-2010s to regain interesting valuation levels. The subsequent story is always a succession of ups and downs. The key to stock market investing is the average upward trend, from which only patient investors benefit.

Beyond patience, it is essential to resist one’s own psychology. In times of crisis, when everyone is telling you that it is probably “the end of the world” and that the economy will never survive such a shock, it is good to recall the essential lessons of financial history to hold firm and not give in to the sirens of panic, which, in this case, can truly cause you to lose a lot of money. Psychological fortitude, a sound intellectual framework, and… the refusal to sell assets that generate passive income are good sources of resilience during crashes.

Key Takeaways:

- Inflation is only your enemy if your capital and income grow slower than the inflation rate.

- Episodes of sharp market declines are historically recurrent and must be part of your intellectual framework for investing.

- No one can indicate in real-time whether the market is nearing a crash or ready to rally again.

- The “average” investor – at least one aware of their limitations – can easily apply the DCA (Dollar-Cost Averaging) method and invest a fixed amount each month to smooth out the average cost of their investments. This is a less time-consuming method that has proven its worth over the long term.

- Crashes make you feel like a poor investor. That is false. Long bull markets, on the other hand, give you the impression of being a great investor. That is even more false.

- The market redistributes money from the impatient to the patient. Those who sold at rock-bottom prices in 2001, 2008, and 2020, for example, greatly enriched the investors who continued to invest during those periods and held onto their assets.

Let’s recap the initial key takeaways in a few lines before addressing prospective questions:

- Over a two-century period, financial assets have shown relatively stable performance. Stocks have experienced the highest growth but are also the most volatile assets. To explore this point further, it is essential to read the work by Jeremy Siegel¹ referenced in the bibliography.

- This impressive growth of financial assets is explained by the mechanics of compound interest, which every investor should strive to harness. It also calls for patience.

- The specific characteristics of different business sectors allow every investor to focus on the sectors that best align with their objectives, but also with their psychology.

- Understanding the various risks that your investment strategy must account for (inflation, currency instability, economic cycles, and financial crashes) allows you to better prepare for the psychological and practical vicissitudes of investing.

1The Austrian School of economics is a heterodox school of economic thought that emphasizes the spontaneous organization of the economy through the actions of individuals, and is critical of central planning and excessive credit expansion by central banks, which it argues leads to boom-and-bust cycles.